LEFT VENTRICLE AR ATLAS

Interactive 3D Version Available

Explore this anatomy in full 360° rotation with our interactive 3D viewer

View in 3D →TABLE OF CONTENTS

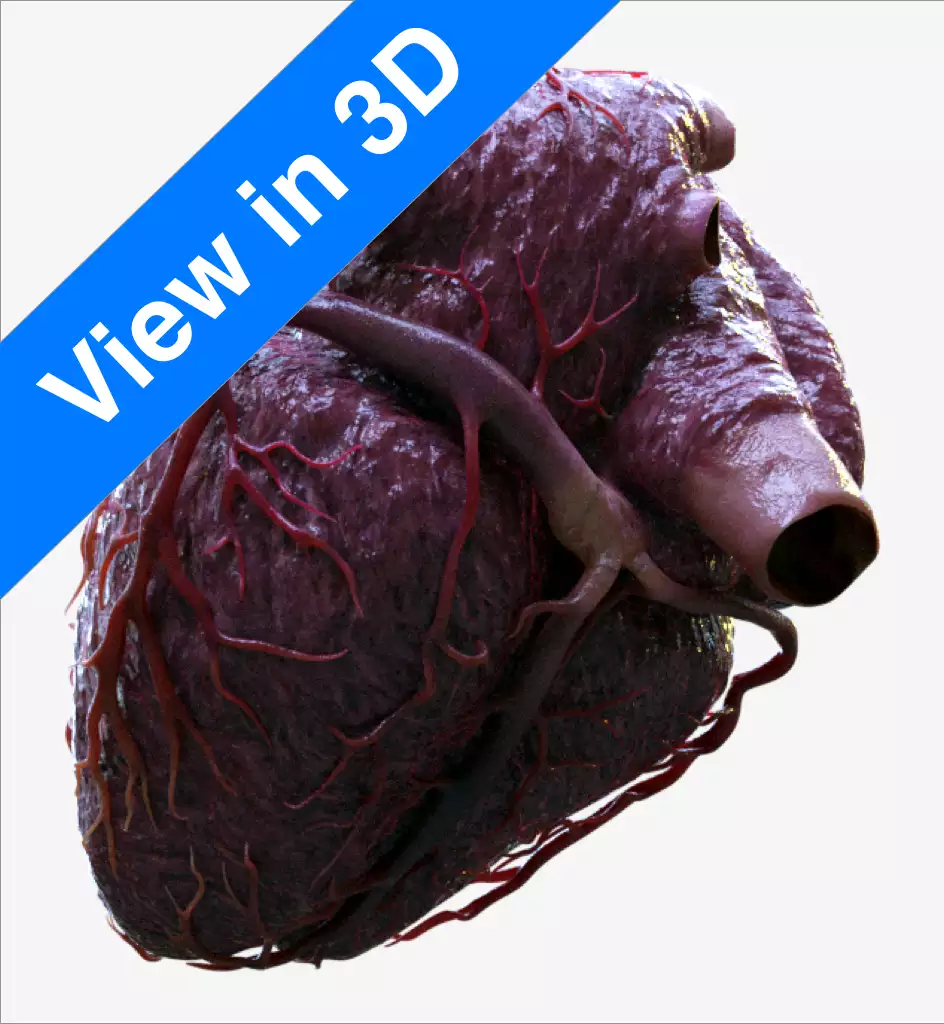

LEFT VENTRICLE

The left ventricle is one of the four chambers of the heart and plays a crucial role in the circulatory system by pumping oxygenated blood to the entire body. It receives oxygen-rich blood from the left atrium through the mitral valve and is responsible for generating the high pressure needed to propel blood through the systemic circulation. When viewed from the front, the left ventricle is primarily situated behind the right ventricle, forming the apex and left border of the heart.

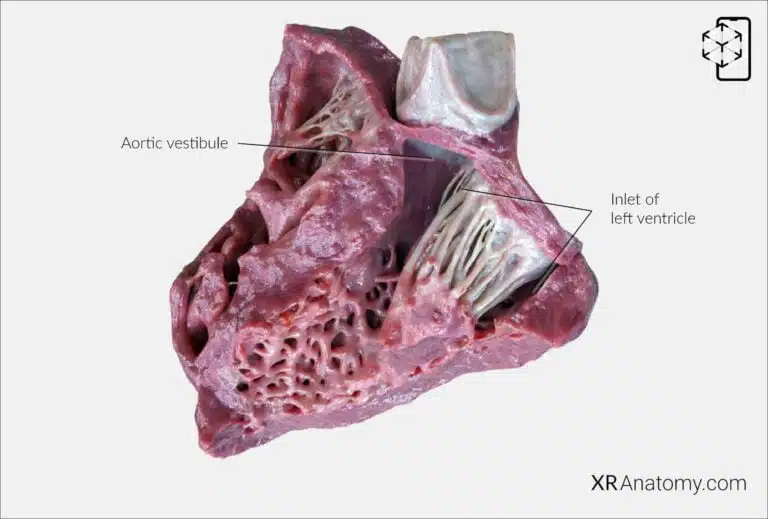

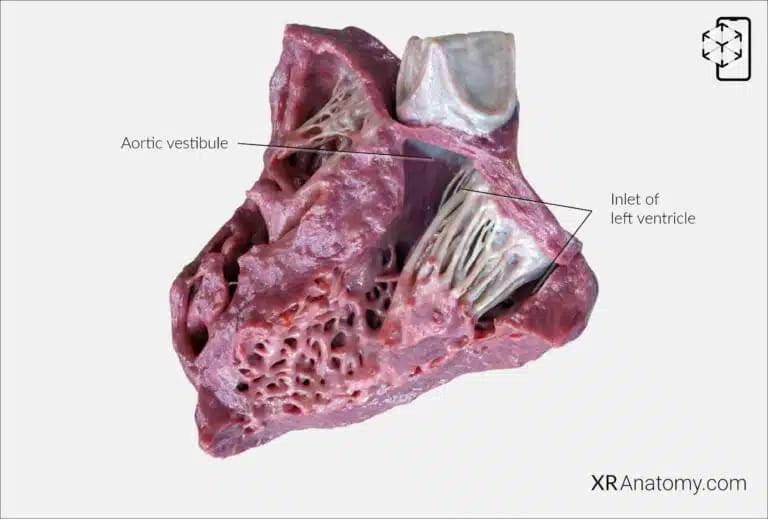

INLET OF LEFT VENTRICLE

The inlet of the left ventricle refers to the region where blood enters the ventricle from the left atrium. This inlet is guarded by the mitral valve, also known as the left atrioventricular valve, which ensures unidirectional blood flow by preventing backflow into the atrium during ventricular contraction. Below the aortic orifice lies the aortic vestibule, a smooth-walled portion of the left ventricle that leads up to the aortic valve. The aortic vestibule helps streamline blood flow from the ventricle into the aorta, reducing turbulence and enhancing the efficiency of blood ejection into the systemic circulation.

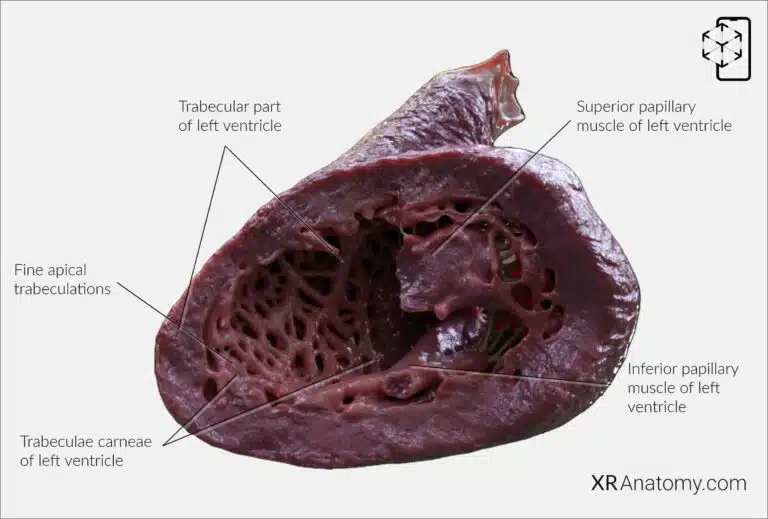

TRABECULAR PART OF LEFT VENTRICLE

The trabecular part of the left ventricle refers to the inner walls of the ventricle that are marked by a network of muscular ridges called trabeculae carneae. These structures enhance the ventricle's contractile strength. The trabecular part extends towards the apex of the left ventricle and is characterized by finer and more delicate trabeculations compared to the right ventricle. Within this region, there are two prominent papillary muscles: the superior (anterior) and inferior (posterior) papillary muscles. These muscular projections play a vital role in the function of the mitral valve by anchoring the valve leaflets via the chordae tendineae, which are strong, fibrous strings. The coordination between the papillary muscles and chordae tendineae ensures that the mitral valve closes properly during ventricular contraction, preventing the backflow of blood into the left atrium.

- The superior papillary muscle is the larger of the two and originates from the lateral wall of the left ventricle.

- The inferior papillary muscle is smaller and arises from the inferior wall near the septum. Both muscles are essential for maintaining the integrity of the mitral valve during the cardiac cycle.

The fine apical trabeculations are delicate, mesh-like muscular structures located at the apex of the left ventricle. These finer trabeculae contrast with the coarser trabeculations found in the right ventricle and are indicative of the left ventricle's adaptation for generating higher pressures required for systemic circulation.

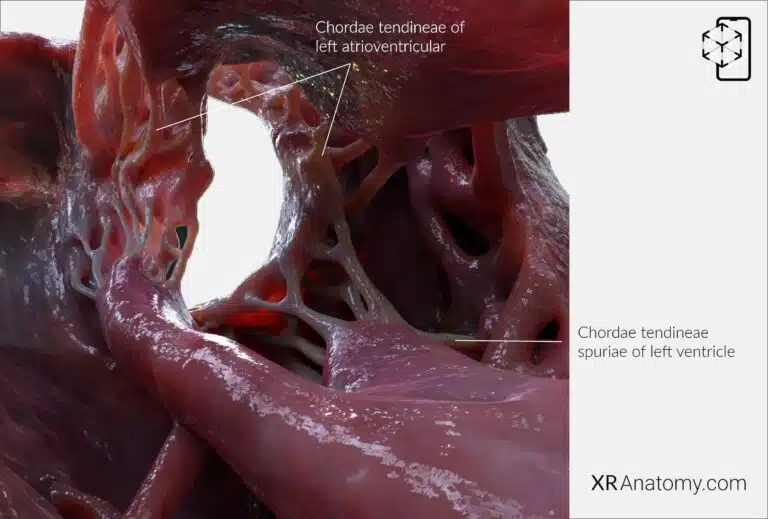

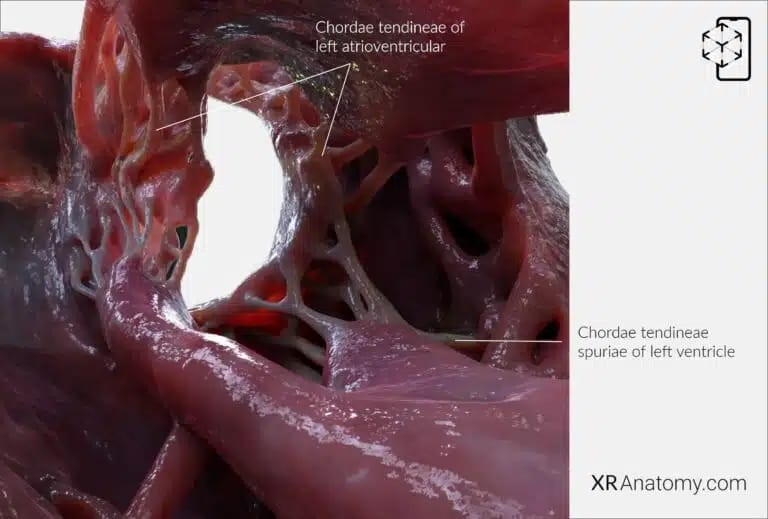

CHORDAE TENDINEAE

The chordae tendineae are essential components of the heart's valvular apparatus, consisting of thin, strong fibrous cords that connect the papillary muscles to the valve leaflets. In the left ventricle, they attach to the cusps of the mitral valve, preventing them from prolapsing into the left atrium during ventricular contraction. This mechanism ensures that the valve closes securely, maintaining efficient unidirectional blood flow.

The left ventricle may also contain chordae tendineae spuriae, or false chordae, which do not attach to the valve leaflets but may span between ventricular walls or papillary muscles.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Gray H, Lewis W. Angiology. In: Anatomy of the Human Body. 1918. p. 526–542.

2. Gosling JA, Harris PF, Humpherson JR, Whitmore I, Willan PLT. Human anatomy: color atlas and textbook. 6th ed. 2017. 45–58 p.

3. Anderson RH, Spicer DE, Hlavacek AM, Cook AC, Backer CL. (2013). Anatomy of the cardiac chambers. In Wilcox’s Surgical Anatomy of the Heart (4th ed., pp. 13–50). Cambridge University Press.

4. Fritsch H, Kuehnel W. Color Atlas of Human Anatomy. Vol. Volume 2, Color Atlas and Textbook of Human Anatomy. 2005. 10–42 p.

5. Moore K, Dalley A, Agur A. Clinically Oriented Anatomy. Vol. 7ed, Clinically Oriented Anatomy. 2014. 132–151 p.

6. Ho SYen. Anatomy for Cardiac Electrophysiologists: A Practical Handbook. Cardiotext Pub; 2012. 5–27 p.

7. Standring S, editor. Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. 41st ed. London: Elsevier; 2016.

8. Moore KL, Agur AMR, Dalley AF. Essential Clinical Anatomy. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2015.